2025-8-26

(Courtesy of Taiwan Panorama August 2025)

Cathy Teng /photo by Xie Xintian /tr. by Jonathan Barnard

Though you may never have set foot on Yushan, you have almost certainly seen it. Pull out a NT$1,000 note, and on its back you will see an image of Yushan’s majestic, snow-capped Main Peak.

You may wonder: Where was the original photograph of this 3,952-meter peak, Taiwan’s highest, taken from? The answer: the weather station on Yushan’s North Peak.

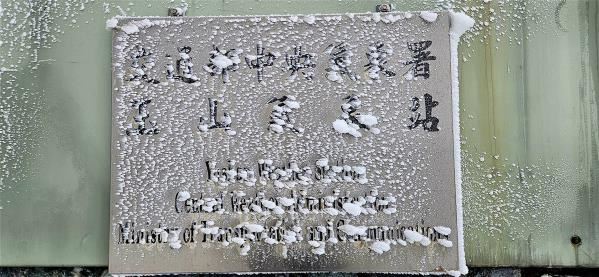

Perched at an altitude of 3,858 meters, the Yushan Weather Station has been staffed by employees on long-term assignments ever since it was built in 1943. One of these, Xie Xintian, worked there for 29 years. He has given Taiwan Panorama an inside look at life at the top of the island.

Logging data at war and at peace

The Yushan Weather Station was founded at the end of the Japanese era. “At first the Japanese wanted to gather high-altitude weather data to conduct their air war in the Pacific,” explains former station employee Xie Xintian, who is now caring for his grandchildren in retirement. “They established observation and measurement stations from sea level to nearly 4,000 meters at Yushan, Alishan, Chiayi and Tainan. That range of vertical data provided important information for fighter planes.”

Xie once served in the air force as the chief meteorologist at Chiayi Airport. Upon retiring, he was hired by the Central Weather Bureau and assigned to Magong and then Dongji Island, both in Penghu. Not able to spend much time with his family with those island postings, Xie requested a transfer back to Taiwan proper and was assigned to Yushan.

How does meteorology differ at sea level compared to high altitudes? “At sea level the weather is relatively stable,” Xie explains, “and unless there is thermal convection in a specific area, there is less disturbance to air flow. But at high elevations, mountainous terrain has a big impact. The great height differences and strong convection currents cause the weather to shift rapidly and dramatically.”

Up on the mountain, work begins at 6 a.m., and data must be logged and reported every three hours. When a sea warning is issued for an approaching typhoon, personnel go into a round-the-clock state of alert, with observational data needing to be reported every hour. Weather stations must record information about rainfall, temperature, wind speed, direction, and gust strength, as well as relative humidity, UV index, visibility, and hours of sunshine. “The data is entered and transmitted in accordance with World Meteorological Organization guidelines with a five-digit identifier: 46 for Taiwan and 755 for Yushan Station.”

A tough life on the mountain

Xie recalls that the first time he reported to work on Yushan his legs cramped up while ascending to his posting. The trip up and down once a month wasn’t easy. But it was even tougher for earlier facility staff, he says. Before the Alishan Highway and the New Central Cross-Island Highway were built, staff had to walk from Alishan to the Lulinshan Weather Station (today’s Lulin Lodge). Then, after staying the night, they would walk 8.5 kilometers up to Paiyun Lodge and turn onto the Beicha Trail to ascend to the North Peak. Just getting to your workplace took two days.

Early on, daily necessities had to be carried up the mountain on foot. Later, helicopters began to be used for resupply during the snow season. But all food up there is precious, and particularly vegetables, since they don’t keep well.

In the 1990s, the Yushan Weather Station faced power shortages. Assistants had to descend two or three kilometers into a valley to find dead wood for boiling water and cooking. Candles were used at night. Later, to solve these issues, charcoal was transported up the mountain and solar panels were installed.

For water, they relied on rainfall and melted snow. Early on, due to a lack of sufficient storage facilities, every drop had to be used with utmost care. It wasn’t until 1996, when the Central Weather Bureau funded the purchase of 12 stainless-steel tanks, each capable of holding 1,000 liters of water, that the water storage problem was finally resolved.

The Yushan Weather Station originally used a wooden building constructed during the Japanese colonial period. In 2000 it was finally replaced with a steel-structured facility and given the address “No. 1, Yushan North Peak.” But don’t try mailing anything there—it’s not on any mail carrier’s route.

Front lines of disaster relief

Standing on the roof of the island, how far can the eye see?

“You know that the Main Peak of Yushan sits mostly within Nantou County,” says Xie. “On a clear day, you can see the summit of Xueshan [on the border between Miaoli and Taichung] to the north, and to the south, you can see the partially obscured peak of Mt. Beidawu [on the border between Pingtung and Taitung]. You can even make out Kaohsiung’s 85 Sky Tower and the Ferris wheel at E-Da Theme Park with the naked eye.”

Situated at the highest point on the island, the station offers great line-of-sight views, Xie explains. Although all weather stations are now equipped with automatic data reading systems, the importance of the Yushan Weather Station is still beyond question. “Did you know that before the National Airborne Service Corps [NASC] sends a rescue helicopter up to Mt. Nanhu, Taiwan’s fifth-highest peak, they always consult the Yushan Weather Station first about weather conditions.”

Down on the plains at Chiayi Airport, where the NASC and the Air Rescue Group of the ROC Air Force often conduct high-altitude training, they usually check the weather a day in advance before scheduling training activities. After years of working together, there is close communication and camaraderie between those on the mountain and those below. Pilots sometimes help out by transporting fragile eggs, heavy watermelons, and other supplies up the mountain, adding nutrition and flavor to life at the summit.

When mountain rescue is needed, the Yushan Weather Station also provides timely support. Sometimes, when multiple agencies need information about weather conditions on the mountain at the same time, station staff start a live stream to share footage and data with everyone simultaneously.

Mountain climate

On Taiwan’s roof, many of the scenic views are fleeting. Inspired by the photographer Chen Bingyuan, Xie picked up a camera to document every scene and detail up there. He notes that the hardest time is snow season. The weather station once recorded an accumulation of 280 centimeters of snow. When the snow comes, it covers the solar panels, and workers have to manually clear the frost in the freezing cold to ensure the panels function properly. It’s tough and demanding work.

But snow season is also Xie’s favorite thanks to the changing colors of sunrise and sunset, which provide fantastic shots. He has also photographed ox-eye daisies blooming on the North Peak, ice-covered Taiwan edelweiss, and proud Yushan juniper. The clouds high above dramatically take the blue sky as their backdrop, shifting colors with dawn and dusk.

The mountain’s fauna has also entered his lens: Taiwan rosefinches, Formosan laughing thrushes, Formosan sambar deer, and yellow-throated martens have all shown it their charm. He once even captured a sambar deer standing among the instruments at the observation platform, with Yushan’s Main Peak and East Peak in the background under a starry sky, while a shooting star streaks toward Yushan’s Main Peak. It was truly a once-in-a-lifetime moment to capture.

Warmth of spirit at 3,858 meters

In recent years, climbing Yushan has become a nationwide craze. After reaching the Main Peak, if hikers still have the energy, some will continue to the North Peak to conquer another summit and visit Taiwan’s highest weather station along the way. If they happen to meet staff on duty, they are often treated to a cup of coffee or hot water—a custom started by Xie. “Giving out coffee on the mountain is a bad example I set,” he laughs.

In the early days, resources on the mountain were scarce. Hikers had to gather firewood themselves to boil water, and availability of water depended on nature’s whims. But he always thought, “A hot drink, a cup of coffee, is precious to climbers who have trekked for hours.” He paid out of his own pocket to buy beans and generously shared brewed coffee with passing hikers.

Many hikers who once had a cup of coffee at the weather station, upon returning to the mountain and passing by the North Peak, would hang a bag of coffee beans on the weather station’s doorknob, along with a note. These small gestures truly reflect Taiwanese hospitality.

When Xie was about to retire after 29 years at the station, many hikers made their way up the mountain to visit him.

A mountain peak, a weather station, a cup of coffee in the wind and snow. What’s being passed along is not just warmth, but also the thoughtfulness and sincerity that Taiwanese people still offer to strangers. Yushan has never been just a 3,952-meter peak, nor merely a scenic image on a banknote. If the chance arises, let’s meet up there at the island’s top, share a cup of coffee, watch the sunrise, and together experience one of Taiwan’s most majestic and heartwarming scenes.